The passage of the “Tax Cut and Jobs Act” in 2017 means that it is unlikely that extensive discussions of tax reform will be meaningful. Advocates of tax cuts (primarily Republicans) are unlikely to sustain any further cuts in the near future, given the Act’s price tag of about $1.5 trillion over the next 10 years. Opponents of the Act (primarily Democrats) will stick to their message points that it will lead to cuts in Social Security and other programs, while Republicans will champion the Act’s contribution to jobs and economic growth. Although there is some truth to all of these points, there is not much, nor do many taxpayers appear to believe them. They are just political selling points.

Of course tax cuts do put money in the hands of taxpayers. The main argument is how to distribute this money. The starting point of the tax cut was to reduce taxes on corporations to promote hiring and increase global competitiveness. There is not actually much disagreement about this, as the Obama administration had also proposed reductions in corporate taxes.

As the corporate tax cut is also the most expensive part of the Act over the long term, many progressives argued that the bulk of additional benefits should go to working and middle class taxpayers and their families. However, conservatives tended to favor “job creators”, so the bill ended up including benefits for “pass through corporations” (privately-held companies in certain industries), heirs in wealthy families (by raising the inheritance tax exemption to over $11 million while preserving the “step up” in basis on appreciated assets), and eliminating the alternative minimum tax, an arcane system originally designed to prevent rich people from avoiding taxes but which because of bracket creep had become a bane for the merely affluent.

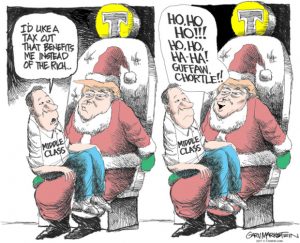

The Tax Cut and Jobs Act also had some benefits for taxpayers who aren’t rich and who don’t earn a lot of income, but even on a percentage basis these benefits are generally smaller than the benefits for wealthier individuals. In addition to getting most of the dollar value of the individual tax cut, the wealthiest taxpayers are also much more likely to benefit dollar-wise from the other provisions of the Act, such as the reductions in corporate taxes (as lower-income taxpayers hold very few shares, and when they own “pass-through” entities they are very small ones), and are much more likely to be heirs.

“Supply-side” conservatives (those who generally favor economic policies that reduce the tax burden on the wealthy and large corporations) always point out that tax cuts favor the wealthy because the wealthy pay more taxes. They also point out that corporations can use some of the money from the tax cut to hire workers and to invest, and that wealthy individuals will invest some of the money (and of course, they can spend some of it). These actions by the wealthy and by corporations can lead to increased economic growth and more jobs.

In addition to tossing in the “pass through” and inheritance tax reductions, which have big ticket costs without much of a return to the economy, the authors of the Act made another big political move, by eliminating much of the deduction for state and local income taxes. Although they came up with arguments for this, it made the Act unpalatable for many by appearing to punish some of the merely affluent taxpayers in states with high income and property taxes (almost exclusively “Blue” states) in order to reward the merely affluent in Red states. This makes it easy for political opponents of the Tax Cut to say that its politically-motivated authors decided to use higher taxes on Blue states to pay for a big cut in taxes on the estates of the wealthiest Americans.

While there are many pros and cons to the Act, there is no question that many of its components, particularly the treatment of state and local taxes, were largely political.

I live in the District of Columbia, and my wife owns a company, so we pay high taxes. At best, we will come out about even after the “Tax Cut” because of the big effect of eliminating most of the state and local tax deduction, which offsets the reduction in our rates. My wife’s company is a services firm, and professional services firms are generally excluded from the benefits of reduced “pass through” rates. However, I do not believe we (meaning the U.S. as a whole) would have been better off without the tax cut. Time will tell. I simply believe that the U.S. as a whole could have been much better off if the bill had not intentionally selected winners and losers for political reasons. Here’s what I mean.

The idea that reducing taxes on the wealthiest estates in the country is “fair” is one of the least fact-based concepts in all of public policy. To say “we believe that our wealthiest political donors should be rewarded for their hard work” would be more honest. It might also be honest to say “we believe that rich people must have contributed more to our country, otherwise they would not be rich”. However, the two justifications that were put forth most often for reducing inheritance taxes were (1) it eliminates a burden on small farms, and (2) it eliminates “double taxation” because taxes may have already been paid on the wealth before it has been passed on.

These two justifications are basically invalid. Very few family farms are subject to inheritance taxes, and those that are have to have already produced quite a bit of wealth. And the law could easily be written to protect family farms without giving big rewards to money that is passed from generation to generation. With respect to “double taxation”, it is a good point, but also not really valid. The Tax Cut and Jobs Act, in addition to eliminating inheritance taxes on estates under about $11.4 million, also maintains the “step up” for appreciated assets. This means, for example, that someone can start a product business, operate it as a pass-through, paying lower taxes than other earners (including possibly employees of that business) and then leave it to his/her now-wealthy heirs, without the government ever receiving any tax income on those $11 million. It seems really hard to make a fairness argument for this.

With respect to the “pass through” preference (a 20% deduction for income for owners of certain private businesses), which had not been part of many proposals prior to President Trump’s, much of the rhetoric treated pass through corporations (such as partnerships, limited liability corporations, and S corporations, which are owned by a few individuals who pay taxes on corporate income as if they’d directly earned it) as if their relative taxation and contributions to the economy were the same as C corporations (especially multi-national public companies). They are completely different in many respects. Fundamentally, if an individual (as opposed to a retirement plan or other nontaxable entity) owns shares in a C corporation, the company pays tax on its income, then the shareholder pays tax if and when the income is distributed as a dividend. Thus the shareholder’s individual effective tax rate combines two levels of taxation, at least in many cases. With an S corporation or other pass through, there’s only one level of taxation; the same tax rates apply to all profits, whether they are distributed as dividends or not, and there is no separate tax on the dividends. Also, because the shareholders of an S corporation or other pass through are the same as those paying all of the taxes, any decisions they make regarding certain corporate investments (particularly hiring) can serve to lower their taxes, so one can make an argument that lower taxes on pass throughs reduce the tax benefits of hiring, rather than promoting more hiring. Further, the pass throughs already enjoy numerous tax advantages, and if these were somehow not good enough, they could always change their tax status to C corporations. Finally, the unique and seemingly arbitrary new treatment for pass throughs in the tax code raises red flags since the President proposed the idea and his family controls hundreds of pass throughs – the special pass through provisions in the tax bill can be seen more as a kickback than as public policy.

When the Tax Cut and Jobs Act was in the final throes of committee markup, there was not much time to work out a lot of the details. The President had said that services firms such as lawyers and accountants shouldn’t enjoy a big tax cut, and certainly no one wanted to create a loophole whereby relatively well paid self-employed or otherwise employed individuals could somehow convert their income to pass through income to get a lower tax rate (it would only really apply to people earning good income). So the committee re-used definitions that were parts of other provisions of the tax code that distinguished service businesses from product businesses, adding, at the last minute, a strange exception for engineering services (such as designing bridges and buildings).

The result is that wealthy individuals who own product companies will pay significantly lower taxes than those who own services businesses, even if those businesses are otherwise comparable, say, they each produce $100 million in income and employ 1000 skilled individuals. The implication is that product companies create more jobs and more value for the economy than services businesses, which may resonate well with strategically-placed voters in manufacturing areas but isn’t really true in the modern economy, where there are more new services jobs than product jobs. It is hard to characterize what makes a good job in this way.

Like any other bill that is passed under political pressure without widespread support (no Democrats supported the bill, and some House Republicans defected after the punitive limitation on state and local tax deductions was added), the Tax Cut and Jobs Act has flaws. It awards hundreds of millions of dollars to wealthy individuals and heirs who do not necessarily do much to create jobs, earn a living, work hard, or otherwise contribute directly to economic growth, and it pays for this in part by giving back more to residents of low tax (predominantly red) states than to residents of higher tax (predominantly blue) states. It is probably not worth arguing about, because it is probably here to stay. However they might complain about being first punished and then left out, Democrats are unlikely to try to repeal the measure, because no one likes having their taxes raised. Plus, some key provisions, such as the reduction in corporate tax rates and the repeal of the alternative minimum tax, were a long time in coming and should stay. Others, such as some of the pass through deductions and reduced taxes for wealthy heirs and heiresses, do not make as much sense, but is very hard to take a financial gift away once it’s been given out by Congress. So the most vulnerable part of the bill is the limitation on the deduction for state and local taxes, which representatives of blue states could try to eliminate (thus forcing conservatives from red states to oppose a tax cut, which they don’t like to do). Otherwise, this is a done deal, and it is I expect the last major tax cut that will be passed during a long period of relative prosperity during my lifetime.

Given that taxation is unlikely to change much, what other lessons can be learned? I believe that the biggest flaws of the Act could have been eliminated, or at least reduced, if there had been any real bipartisan dialog and debate. But there wasn’t. Republicans simply championed it and Democrats mainly complained that it is too generous to the rich. It is too generous to the rich. Had it been a bipartisan effort, it could have been more balanced, less punitive, more cost effective, and even larger (because of budget reconciliation rules). If, as the administration argued, the tax cut would pay for itself in economic growth, then an even bigger tax cut would have been even better. However, because of politics, Republicans preferred to have sole credit for the tax cut and ride it as their crowning achievement going into the midterm elections in 2018, while Democrats decided to focus on how Republicans give handouts to the rich and criticize their supposed intention to cut social programs in the future.

If we were ever to move toward an improved version of the Tax Cut and Jobs Act, it would revisit and clarify the treatment of “pass through” companies, and possibly eliminate the “step up” in basis for inherited assets, which allows wealthy heirs permanently to avoid taxes now on at least $11 million in inherited assets even if those assets have never been taxed, ever. This could be balanced with a further expansion of the Earned Income Tax credit and possibly other tax cuts that benefit struggling workers. It would make sense.

As with other aspects of government budgeting and spending, we would be much better off if these complex issues were dealt with by non-partisan or bipartisan or otherwise balanced groups, but they are not. I do think as voters we should not give our representatives a “rubber stamp” and concede that they must work only with their own party. We would all be better off if they didn’t.