With this whopping, complicated, confusing, expensive issue, we’re going to start with the Affordable Care Act (also known as Obamacare) and then turn to Medicare, which will soon outpace military spending as a percentage of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP).

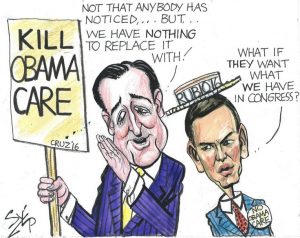

In 2017, after years of messaging that Obamacare was a “train wreck” and numerous congressional votes to repeal the Affordable Care Act, a Gallup Poll showed for the first time that the majority of Americans approve of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Ironically, a higher percentage, according to some surveys, approve of the ACA than approve of the same act when it is called “Obamacare”, because evidently a significant portion of Americans do not know they are different names for the same thing. This is ironic, because, of all the most popular parts of the ACA (e.g., requiring insurance for those with pre-existing medical conditions, allowing students to remain on their parents’ plans, etc.), the “affordable” part is one of the weakest. It is hard to argue that the ACA has succeeded in making health care more affordable, although some say that it could have gotten even more expensive even faster had the bill not been in place. In any case, it is highly unlikely that Americans now approve of the bill because they have decided their health care is more affordable; rather, they approve of parts of the bill and are unconvinced by the critics that it is a “train wreck” because they probably know that much of the criticism is just politics as usual. Further, one of the most unpopular and controversial parts of the ACA, the “individual mandate”, which imposed penalties for individuals who do not purchase insurance, has been repealed (as part of the 2017 Tax Cut and Jobs Act). So, in a strange set of events, the ACA has become more popular and efforts to “repeal and replace” it have failed at the same time that many of the fundamental deficiencies of the bill (such as health care costs that have continued to escalate and the associated low participation rates of younger, healthier people in the program) have not been corrected. While arguments for and against the ACA will largely match political alignment, it would be very hard to argue that we could not do better if we were not fighting so much.

Let’s start by addressing the key issue of “affordability”. All you have to do is look at the names of acts of Congress and you can see that they often express wishful thinking: A bill that expands health care coverage is called “The Affordable Care Act” and a $1.5 trillion tax cut is called “The Tax Cut and Jobs Act”. While the theory behind ACA was that having more people participating in the insurance pool (by virtue of the huge, required expansion of the number of individuals covered by insurance) would help to control costs, this was only theory. In practice, this part of the bill basically failed mostly because not enough healthy people sign up for insurance (of course, the aim of the hated and now-defunct individual mandate was to force healthy people to carry insurance, effectively helping to cover the costs of the not-so-healthy). Similarly, the “Tax Cut and Jobs Act” is a tax cut that in theory will help to create jobs. We have to wait and see whether it will make it any easier for those who now cannot find a job (already at historically low percentages) to get one.

The ACA clearly succeeded in expanding health coverage (extending insurance coverage to approximately 20 million Americans), which is the main reason why efforts to “repeal and replace” failed. Every replacement that was proposed in “repeal and replace” would have reduced the number of people with health insurance, and it was not even clear how or why the proposals would help to control costs. Perhaps the most non-sensical and purely political notion is that health care is more “affordable” if you eliminate the requirements for coverage of certain costs and conditions. The most controversial and politically provocative of these is maternity & newborn care, which is economically one of the best investments a developed nation can make but is politically charged because many men like the idea (in theory) of paying less for insurance by simply opting out of maternity coverage, which they will never need. But insurance doesn’t work this way because it pools all of the costs and risks. So if we eliminate some or all of the requirements it will not accomplish the objective of reducing overall costs, and, even more importantly, if many individuals get to buy cheaper insurance because that insurance covers less, it is not really more “affordable” — it is just cheaper. It’s like paying less for a rental unit that doesn’t have hot water — “affordable” is a bit misleading because it’s missing a feature.

In the fog of alarming, misleading and confusing political messages, people haven’t gained much of an understanding of our health care system, or at least of how ACA works. At a basic level, we have to think of affordability and cost in terms of what we are getting for a price, not simply the cost of insurance. If you don’t have insurance, insurance is cheap–free–but your cost of getting medical treatment will most likely send you into personal bankruptcy if you need it (medical bills and divorce are the two leading causes of bankruptcy). I don’t think failing to pay bills and declaring bankruptcy falls into the category of making health care affordable, but that’s the way it’s treated if you just look at the cost of insurance. Similarly, if you have cheap insurance that doesn’t cover what you need, the insurance is affordable but not the health care.

Most importantly, if we spend more and get a better product, that doesn’t mean that health care is less affordable. We can only measure affordability when we talk about the price of comparable products. In some ways, given that we are living longer, healthier, more active lives, in part due to life-saving and life-prolonging medicines and incredible advances in medical procedures, it is simply invalid to say that health care costs are “through the roof” just because we are spending so much more. We are spending more, and we are getting a longer-living, healthier country as a result. Nearly all of my oldest relatives have had cataract surgery, often used as an example of how expensive medical care can be (and how lucrative for practitioners). It can take 10 minutes and cost $5000 or more. But my 85-year-old mother can drive at night after cataract surgery, and my 85-year-old father in law can for the first time in his life see perfectly without glasses. How much is it worth to get and keep your vision, with a decreased risk of complications? It is simply invalid to try to argue that health care is too expensive because the costs go up too much, when a good part of the cost goes to a product for which we would gladly pay anything we have, whose quality has improved, and which in all likelihood didn’t even exist before.

So our discussion as citizens has to turn to continuing to expand health coverage, improving the quality of health care, and controlling costs as much as possible. Of the 900-or-so pages of the text of the ACA, a good number are regulations aimed at health care quality, and a good number of those are working. Some are not. Turning health care into a political football game has made it impossible to improve the regulations. With respect to costs, we could be taking numerous steps to solve the biggest problem with ACA, i.e., that people who need insurance the most and are most likely to cost the system are the ones who are signing up, so we’ve got an imbalance. The rhetoric certainly doesn’t help getting people to sign up, especially since the individual mandate has been repealed. Finally, politicians from both parties promised to give the public more options for health insurance. Yet the public is getting fewer options. The blame is certainly shared, but we shouldn’t be electing politicians whose best strategy is to blame someone else. They should at least be making progress.

In addition to many other possibilities to make ACA work better, a topic that frequently comes up is the so-called “public option”, sometimes under the guise of “medicare for all”. Many point out that members of Congress get good health insurance through the government; why not make this program (or something like it) available to everyone? This possibility is often met by the criticism that it is “socialized medicine” (the word “socialist” in this country is usually meant as an insult) or that “the government shouldn’t be in the health care business”. Some of my most conservative friends take the point of view, “the government shouldn’t be in the health care business, but we already are, so as long as we are, we may as well get as much for our taxpayer dollar that we can”. In other words, it doesn’t matter what you call it. The point is to make it work. Right now the U.S. leads the world in military might and many measures of financial success; we lag most developed nations in health care accessibility, affordability, and overall health (as evidenced, for example, by infant mortality, rates of diseases like heart disease and diabetes, and life expectancy). We can argue about what role the government should have, but this is a sort of moot, theoretical argument at this point: the government is in it, we’re paying for it, and we’re not going to be able to change that any time soon. So, of course we should demand that our government do a better job!

Turning now to a brief summary of the issues with Medicare, also a complex program and a political minefield, the most pressing problem is similar to that of Social Security: As costs continue to rise (in part because people are living longer and there are more of them covered by Medicare), there’s an expected shortfall in the government’s ability to cover the costs. There are numerous other issues with Medicare, such as the difficulty for some seniors to make good informed choices in the face of complexity, and the potentially increasing number of physicians who refuse to accept new Medicare patients as the number of patients increases. Of course we all want to improve quality of care and reduce fraud and abuse. But politicians have basic disagreement over how to approach the cost problem: conservatives tend to like some form of vouchers and/or privatization, or possibly increasing co-pays or deductibles. Democrats (such as Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders in 2016) often want to expand Medicare but often neglect details such as how to cover the costs. Each side accuses the other of trying to “end Medicare as we know it”, because at this point we literally cannot live without it. We are quite far from anything like a comprehensive set of improvements, although improvements are necessary.

As with Social Security, the best we can do is to ask our representatives to favor practical approaches over rhetoric, and be willing to compromise in order to improve the system, rather than just protecting our political turf.