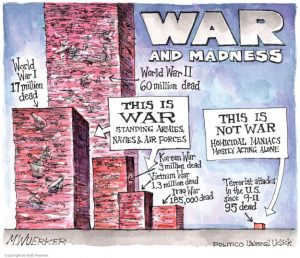

Depending on how the money is counted, U.S. taxpayers have spent between $2 trillion and $6 trillion on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. About 7,000 Americans have died in these conflicts, far more than on September, 11, 2001, with hundreds of thousands of civilian casualties, some the unfortunate but inevitable result of actions by our military and associated personnel.

Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden are dead. Al Qaeda seems to be no longer a real threat, and the threat of ISIS is receding. However, no one has declared victory in the so-called “war on terror” and few will argue that all of our trillions of dollars have been well spent, especially given the lives that have been lost (and continue to be lost) and the still-swelling number of casualties.

War is not a matter of policy, or of political orientation. But it is political. Once our leaders send our troops into war, they tend to escalate, and the American citizen can become collateral damage. Official lies are told, official crimes are committed, and often citizens are mistreated. Domestic law enforcement often suffers. Political “enemies” become enemies, and can lose their civil rights. Without going into a thorough review, we have the Japanese internment in WWII (and the famous Supreme Court cases that resulted), the secret bombing of Cambodia, the Pentagon Papers (and the story behind them, where the Department of Defense had consistently deceived the Congress and the American public in order to justify sending more American troops), the Valerie Plame affair and the associated misinformation accompanying our sending troops into Iraq, and nearly 20 years of actions in Afghanistan, which did not ever capture bin Laden (he was killed in Pakistan).

Very few politicians have the courage to stand in the way of escalation when it starts, although a great many will claim to have been opposed to it (or to have been deceived) afterwards. The “Iraq Resolution” in 2002, one of the few cases where there was political discussion of a pending war, received the support of 69% of the House and 77% of the Senate, including the majority of Democratic senators such as then-senators Hillary Clinton and Joe Biden. Various proposed amendments to the Iraq Resolution, including trying to work with the United Nations to ensure that Iraq did not have weapons of mass destruction (in the end, none were found), and authorizing the use of U.S. armed forces only in the event of imminent threat from weapons of mass destruction (in retrospect, there was no threat, as no such weapons were found), were overwhelmingly defeated.

You may not think this was a mistake, but the majority of us do think the Iraq War was not worth the cost and loss of life, and the majority would rather that our troops were not still in Afghanistan. How do we as voters contribute to these decisions?

Wars are not political, but I believe politicians do support wars for political reasons. They make the crucial decision because they don’t want to appear weak or unpatriotic, and then they support escalation because they don’t want to admit a mistake. And they do this because our culture rightfully honors the military and military service and does tend, as a result, to glamorize conflict. So we as voters tend to associate support for war with support for the military, and we should not do that.

There is, unfortunately, little we can do, because we will inevitably go to war again and the costs in human life and dollars will almost certainly be even higher. But what we can do as citizens is to recognize that we can be devoted patriots and support our troops without supporting military action, we can honor (and not punish) our representatives for having the courage to stand against war, and then we can vote them out if they send our service personnel senselessly into battle (that is, if we believe the action was mistaken).